A Seattle fertility doctor has surrendered his medical license after facing accusations that he used his own sperm to impregnate a California woman while he was treating her as a fellow at UCSF 15 years ago.

IVAN COURONNE/AFP via Getty ImagesA Seattle fertility doctor has surrendered his medical license after facing an accusation that he used his own sperm to artificially inseminate a California woman while he was treating her as a fellow at UCSF 14 years ago.

The allegation, made public earlier this month, prompted UCSF to send letters to women treated by the doctor advising them of the situation and offering genetic testing for their own families.

Christopher Herndon voluntarily gave up his Washington state medical license on Nov. 29, after resigning in September from the University of Washington, where he specialized in reproductive medicine since 2017. He does not have an active medical license in California.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

UCSF officials said they learned he had surrendered his license and of the allegation against him on Dec. 1, and began contacting former patients Dec. 7. The university has hired an outside law firm to conduct an investigation into Herndon, which is ongoing.

Herndon was a fellow at UCSF focused on reproductive endocrinology and fertility during 2008-11, according to the university. He was a part-time doctor at San Francisco General Hospital in 2011-14, and also in private practice during that time, according to UCSF.

“The actions Dr. Herndon is accused of are inexcusable and we are exploring all legal options against him, including potential civil and criminal actions,” UCSF said in a statement Friday.

Herndon’s case was first reported Dec. 5 by the Seattle Times; his affiliation with UCSF was not made public at that time.

The allegation was reported last summer to the Washington Medical Commission. After its own investigation, the commission decided that Herndon should surrender his license. Herndon agreed to give up the license but did not admit to the allegation.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

According to the former patient’s allegation, which was summarized in a report from the commission, Herndon was working as a clinical fellow in training in California when she was treated by him in November 2009.

The woman had previously used donor sperm for artificial insemination to become pregnant with her first child, according to the medical commission. She’d come to UCSF for the same procedure for a second child, and requested the same donor sperm.

The woman became pregnant, and her second child was born in 2010, according to the commission. Later, DNA testing showed that her two children did not share paternal DNA — they didn’t have the same biological father. Further testing found that the second child was not born from the sperm donor the patient had selected for both of her children.

The woman then signed up her second child with a genetic testing and ancestry service. That service identified a potential family connection with the last name Herndon, according to the medical commission. The genetic match was 25%, meaning the person was a grandparent or aunt or uncle. The woman hired a private investigator, who eventually determined the person she’d found online was a sibling of Herndon — her child’s biological uncle or aunt.

Herndon “replaced the donor sperm” chosen by the woman with his own sperm for the artificial insemination procedure, without the woman’s “knowledge or consent,” the medical commission stated. “This was a purposeful violation of the trust placed in (Herndon) as a physician which had a profound impact on the patient and the patient’s family.”

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Officials with the UW Medicine healthcare system in Washington said they have no evidence of inappropriate behavior while Herndon worked there, but they were also alerting former patients and offering free genetic testing to women who underwent artificial insemination procedures.

“Based on what we know at this time, the safeguards in place at UW Medicine’s medical centers should prevent an incident like the one alleged to have occurred in California in 2009,” university spokesperson Barbara Clements said in a statement Friday. The university has in place “numerous safeguards” including “multiple identity checks, careful chain of custody practices, and separate labs for egg and sperm specimens,” she said.

“We are reviewing our safeguards and procedures to continue to ensure the highest level of specimen security. We do not believe that our patients were at risk.”

Herndon is a graduate of Yale School of Medicine who did his residency in obstetrics and gynecology at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, which is affiliated with Harvard University. Herndon could not be located for comment. The woman who made the allegations has not been identified.

Megan Heller, who underwent fertility procedures at UCSF at the time Herndon was there, said she received a letter from UCSF informing her of the situation on Wednesday. She said the university has offered her free counseling, testing for sexually transmitted infections and genetic testing for her family.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

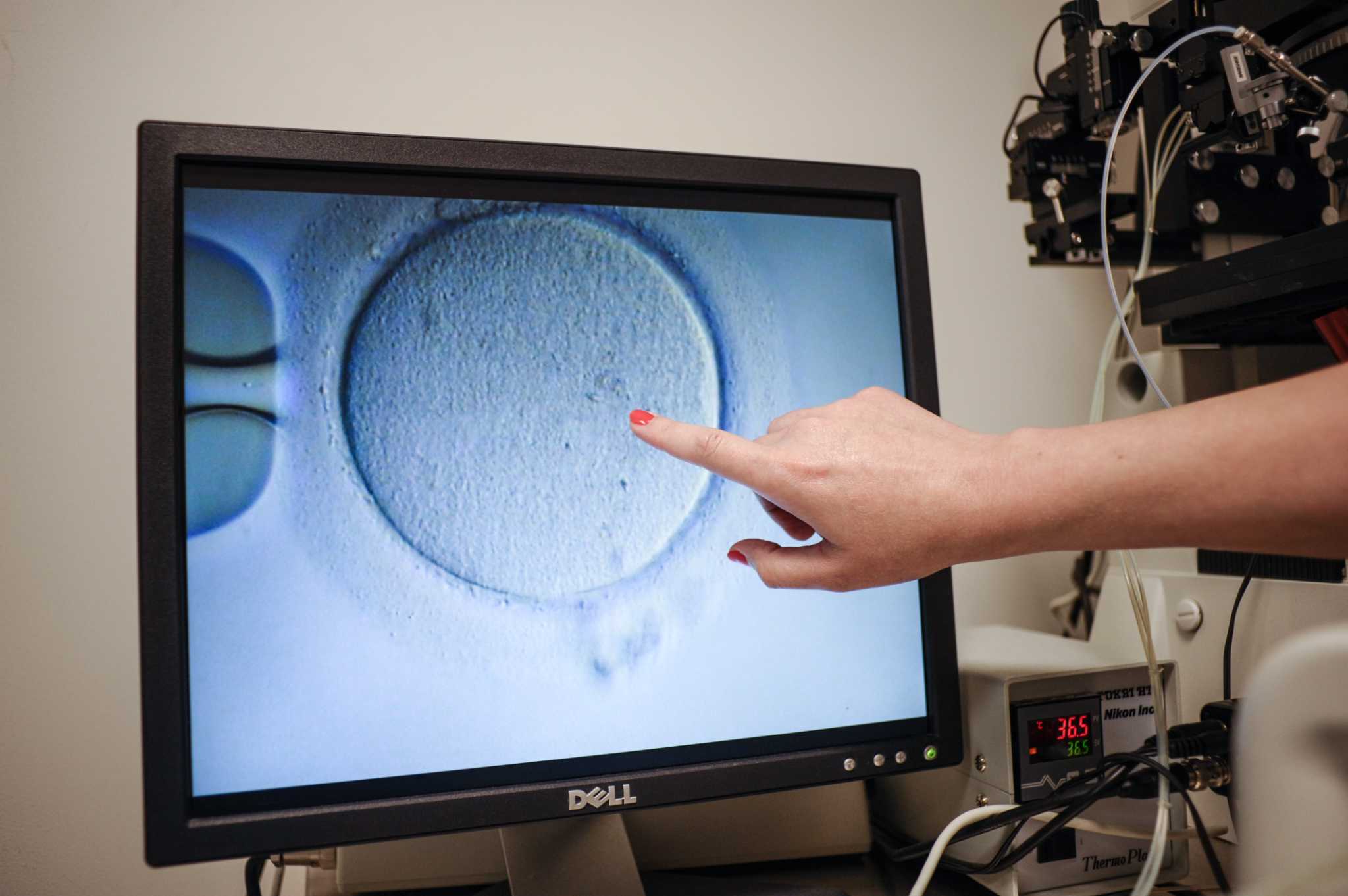

Herndon had performed artificial insemination procedures on Heller, now 43, that did not result in pregnancy. She later used in vitro fertilization, in which eggs are fertilized in a lab and the embryos inserted in the uterus, to become pregnant. Herndon was not directly involved in the IVF procedures, Heller said, though he would still have been at UCSF at the time.

“I did not get pregnant from those particular procedures (Herndon performed), but I did go on to have IVF at UCSF, under the same attending (doctor), with the same group of fellows, and I did get pregnant,” Heller said. “I was unconscious and sedated for so many procedures. I don’t know if (Herndon) was in the room. I don’t know what role he played during his tenure.”

Her son is now 12, and Heller said she plans to use the genetic testing offered by UCSF.

So-called fertility fraud, and specifically cases of doctors using their own sperm to impregnate patients, has been a troubling aspect of reproductive medicine since artificial insemination took off more than 50 years ago.

The practice has become more widely known in recent years with the widespread accessibility of genetic testing. In many cases, individuals have signed up for testing out of curiosity only to find that their paternal DNA isn’t what they expected.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Donor Deceived, a website that tracks such cases, has identified nine doctors accused of using their own sperm to artificially inseminate patients in California, resulting in 18 pregnancies, some dating back to the 1970s. One Indianapolis doctor used his sperm to impregnate dozens of women in the 1970s and ’80s and is the biological father of more than 90 children.

“There are so many unknowns. How did this even happen?” Heller said. “I’m horrified to think of how sloppy protocols must have been for this to have happened. And who’s to say how many times it happened?”

Reach Erin Allday: eallday@sfchronicle.com; Twitter: @erinallday

Source link

credite