It also helped him land a lucrative job.

After the bill passed, officials with the Harris County probation department turned to Whitmire, paying him more than $80,000 to help explain the legal changes. They required probation rather than prison time for some criminals.

The episode spurred two government investigations into whether he was paid with state funds, which would have violated the state Constitution. Neither led to any action taken against Whitmire.

The consulting deal is perhaps the most high-profile example of Whitmire blurring lines between his public and private roles. But it is far from the only one over his half-century in office.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Several other consulting and lobbying gigs in the 1990s produced similar conflict-of-interest questions, leading to various levels of scandal that drew ink in the city’s newspapers – but never any criminal charges. And his work since 1997 at Locke Lord, a prestigious and politically connected Austin law firm that frequently lobbies at the statehouse, has raised potential issues as well.

This obscuring of professional boundaries has made Whitmire an emblem of the Capitol’s hazy ethical culture, a reputation that raises questions about whether similar patterns would emerge at City Hall if he prevails in the Houston mayoral runoff he is favored to win on Dec. 9.

“His career for me exemplifies the things that are both wrong and right with Texas government,” said Jim Moore, an author, consultant and former reporter who covered the Legislature in the 1990s. “He has gotten stuff done, but at the same time, he’s benefited himself both financially and politically.”

Whitmire has said he will quit his job with Locke Lord and stop practicing law if he wins the runoff. And, as he has in the past, Whitmire argued such conflicts are relatively unavoidable in a Legislature that pays its part-time members just $7,200 a year, a far cry from the $236,000 salary Houston mayors earn.

He has said none of his outside contracts affected his work in Austin, and he blames continuing scrutiny of the arrangements on political enemies who have wanted to mar his reputation over the years.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

“If you can pick out an occupation that doesn’t have business in the Legislature, that’d be very surprising,” Whitmire told the Chronicle.”We all have to have a job. You’re hired by the people that you know. You’re hired by the people that think you have some expertise.”

Houston’s mayor has immense power over city government, acting both as a board chair and a chief executive with broad discretion over a 20,000-person workforce and $6 billion budget. The mayor can influence who receives lucrative city contracts, from airport concessions to housing deals to massive public works projects.

Former Houston Mayor Annise Parker, who is backing Whitmire in the runoff against U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, said most city contracts simply go to the lowest qualified bidder.

But, she added, others can come down to more subjective measures like deciding what’s the “best value.”

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

“There are really any number of opportunities for the mayor to put his or her finger on the scale,” Parker said, stressing that she was not casting judgment on either candidate’s ethics.

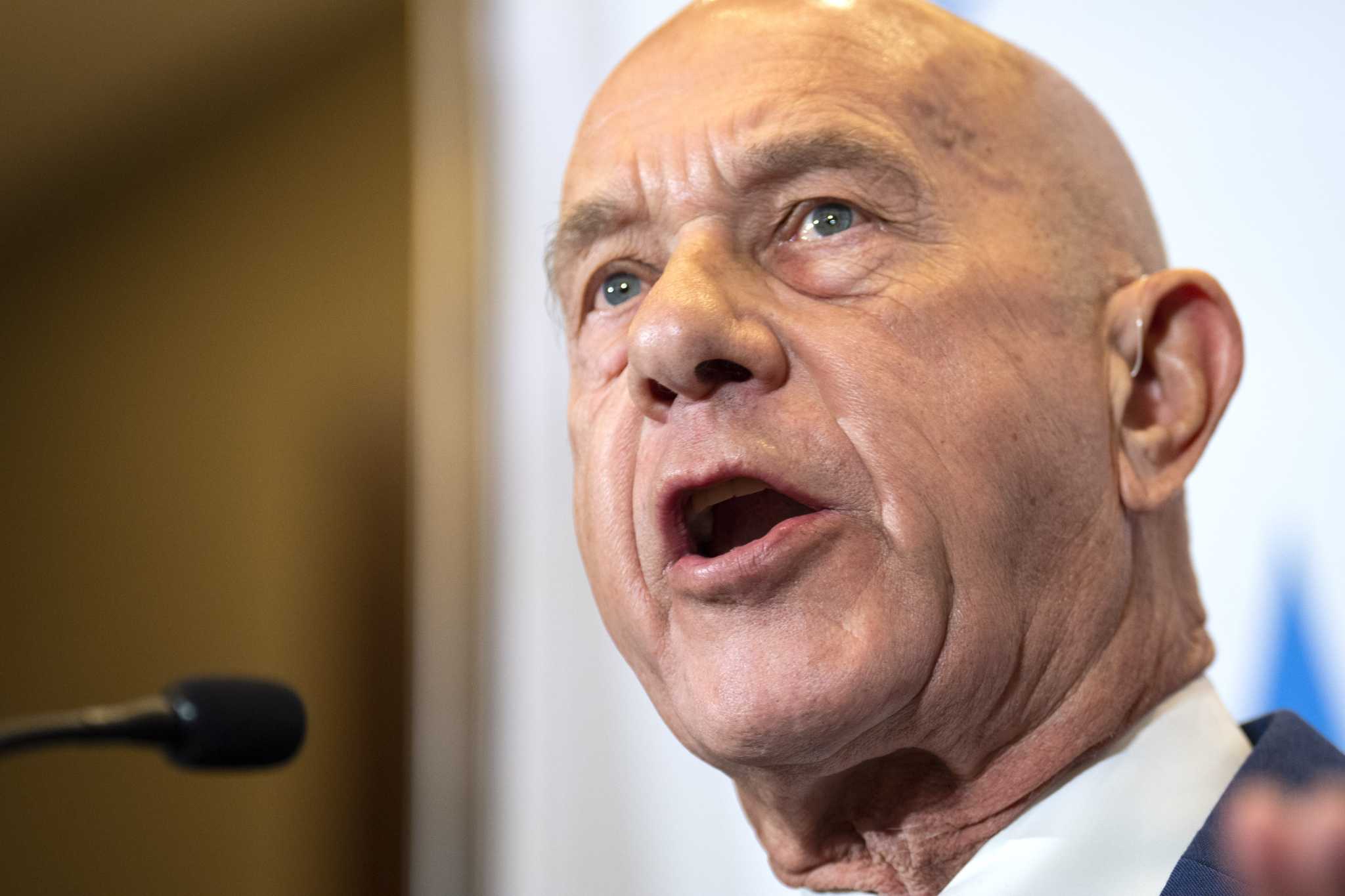

Mayoral candidate State Sen. John Whitmire greets his supporters as he arrives to an election watch party on Tuesday, Nov. 7, 2023, in Houston.

Brett Coomer/Staff photographerPotential conflicts

Close associates of Whitmire could have financial interests at City Hall. His daughter, Whitney Whitmire, is the co-owner of a lobbying and government relations firm that launched after her father announced his mayoral bid. It has recently started representing influential groups at City Hall and in Austin, including some key backers of Whitmire’s campaign.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Whitney Whitmire told the Chronicle the firm would drop its City Hall business should her father become mayor. “That was always the plan,” she said. But four sources who separately spoke with Whitmire or her business partner said the pair had previously discussed their firm potentially continuing to lobby at City Hall.

Two of John Whitmire’s longtime business partners, Andy Schatte and Michael Surface, are Houston developers whose controversial business dealings have been tied up in criminal probes of several Houston and Harris County officials over the years.

Whitmire, who was not involved or implicated in those cases, has held stakes in several of their companies for years, in some cases as recently as 2021, according to state financial disclosure forms. A company Schatte helped create still manages the Hermann Park golf course, a contract that will be up for renewal at City Hall next year. The company is run by Richard Bischoff, Schatte’s business partner with decades-old ties to Whitmire, who did legal work for the company and introduced its principals to Locke Lord.

Bischoff, who contributed $5,000 to Whitmire’s campaign last year, did not respond to a request for comment. Surface and Schatte also did not respond to requests for comment.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Craig Washington, the former Houston congressman and state lawmaker, has been a friend of Whitmire’s since their first election to the Texas House in 1972.

Washington’s political career ended in 1994, when Jackson Lee unseated him in the Democratic primary. Washington initially backed Whitmire’s mayoral campaign, he said – until he spotted Schatte at Whitmire’s Minute Maid Park campaign kickoff in June.

“I told Whitmire, ‘I can’t support you because Andy Schatte is back, and I can’t trust you,’” Washington, who has represented Schatte in civil matters, told the Chronicle.

Washington and Schatte are involved in a separate legal dispute involving the sale of a Midtown commercial building. Whitmire attributed Washington’s remarks to bitterness stemming from that dispute.

On the campaign trail, Whitmire has stressed the need for ethics reform, citing an alleged pay-to-play culture at City Hall underscored by recent controversies during Mayor Sylvester Turner’s administration.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Turner, who has denied any wrongdoing, shot back this week by bashing Whitmire’s own ethical standards.

“To talk about conflicts, my god. You want to talk about conflicts?” Turner, who is supporting Jackson Lee in the runoff, said during Wednesday’s council meeting.

The mayor also suggested Whitmire’s history of ethical lapses could follow him to City Hall.

“What’s your plan? Undo everything and just give stuff away when you get here?” Turner asked as he defended a controversial airport contract that Whitmire had criticized.

Whitmire said his administration would be “the most transparent” in history when it comes to contracting.

History of legislative and financial entanglements

In the 1990s, Whitmire drew scrutiny for accepting private gigs tied to his legislative work. That included an 8-month, $40,000 federal lobbying contract from the Houston firefighters’ pension fund in 1993, months after he successfully sponsored legislation the fund supported.

Whitmire said the two subjects were unrelated, and his lobbying contract did not affect his consideration of bills.

He also was paid $25,000 between 1994 and 1995 to do legal work for the owners of a halfway house that received state funding and was directly affected by laws he helped pass. He promoted the facility to officials at one of the state agencies that funded it, faxing them a copy of the facility’s monthly newsletter with a handwritten note saying, “These people are doing an outstanding job. Please help them to do more.”

At the time, Whitmire said the foundation that owned the halfway house paid him with private funds to represent it on “non-state-related” matters. He said he intervened with the state agency in his capacity as a senator, not the foundation’s attorney.

When the Texas Senate approved bingo legislation in 1989, Whitmire – who represented Houston bingo operators – spoke against provisions restricting the operators. A few years later, when Harris County sued three topless clubs, Whitmire accompanied one of the club’s owners to a meeting with a county attorney, who concluded “he was definitely here to curry some favor on behalf of the club.”

“I think what he meant is I asked him to take a second look at something. If you want to call that ‘currying favor,’ that’s called practicing law to many people,” Whitmire said Thursday. “All I’ve done in every instance … is be a licensed attorney that happens to be in the Legislature, that has political contacts, and I get hired outside the Legislature to fix people’s problems.”

Whitmire also stressed that most of these arrangements occurred in the 1990s. He said he has long since abandoned practicing before state agencies.

“I’m wiser now than I was 30 years ago,” he said.

Andrew Wheat, research director for the government watchdog group Texans for Public Justice, said state and local lawmakers have long permitted themselves to enter into ethically dubious situations, like when local entities enlist the lobbying or legal services of legislators.

“That’s always a bit of a quagmire, because the representative from the Legislature has the business of representing those local governments in their search for funding for various projects,” Wheat said. “That gets into very murky waters very fast.”

Texas Sen. John Whitmire listens to U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee during a mayoral forum on Wednesday, Nov. 15, 2023, in Houston.

Elizabeth Conley/Staff PhotographerWhitmire also was repeatedly questioned in the mid-1990s about whether he was ensuring taxpayers got their money’s worth out of his staff. A Senate committee even enacted new rules specifically to prevent Whitmire’s past practices from continuing.

One staffer was listed as a part-time aide at 32 hours per week. But the man also practiced law for himself – and Whitmire – on the side. He filed legal documents for the senator, and even appeared in his place at court hearings.

Another Whitmire staffer was president of Ironworkers Union Local 84 in Houston and reportedly worked at a Texas City industrial plant at the same time he was on Whitmire’s payroll at $3,000 a month.

And Whitmire paid a Houston engineer $50,000 from 1994 to 1995 to study criminal justice issues, but the consultant produced no written work product.

“All had very valid jobs, produced, and it went away as fast as it appeared because it was all frivolous political attacks,” Whitmire said.

The senator then joined Locke Lord, the politically connected firm, in 1997, three months after working with its lead lobbyist, Robert Miller, to pass legislation allowing Harris County to construct professional sports stadiums.

The firm’s managing partner, R. Bruce LaBoon, said then that Whitmire’s primary roles would include bringing in new clients. Whitmire, however, said he was never a “rainmaker,” and most of his work involves representing clients in legal matters. There is a “wall” between the firm’s lobbying and law arms, he said.

A 2002 Chronicle report said the firm was hired to lobby the Legislature on behalf of the Houston Community College System after Whitmire dined with the system’s chancellor – a lunch scheduled for the purpose of discussing lobbying services.

Whitmire has not publicly disclosed a list of clients, but he vehemently argued that his role at Locke Lord does not sway his decisions in the Legislature. He pointed to his vote this year to bar cities and counties from hiring lobbyists to vouch for their interests at the Capitol — a bill that would have cost Locke Lord business from the city of Houston, which had hired the firm to lobby in Austin.

“You looking for some ethics? I don’t know anybody else who has as strong a record of ethics as voting against my employer,” said Whitmire.

Investing in developers

In the early 2000s, Schatte and his business partners landed repeated big-ticket government contracts. Schatte and Surface’s firm, The Keystone Group, received lucrative construction deals for both the city and county.

The two developers came under federal scrutiny and were indicted in 2008 as part of a scheme to sway city officials with gifts. The charges against Schatte ultimately were dropped, but Surface pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI and received two years’ probation. The city official, Monique McGilbra, was sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison after admitting to taking gifts from Keystone.

Surface also was charged in a bribery scheme with then-County Commissioner Jerry Eversole over roughly $100,000 in cash and gifts. Eversole pleaded guilty to a lesser charge, resigned from office and got three years’ probation. Surface pleaded guilty to filing a false tax return and also received three years’ probation.

Whitmire has continued to do business with the pair. His financial disclosure forms show investments in companies linked to both men, including in 2013, a year after Eversole and Surface were sentenced. He reported interests in Surface’s development firm through 2016.

His reports in subsequent years show investments in companies linked to Schatte through 2021. They included Fort Worth Stadium Group, which sought to redevelop a baseball stadium and surrounding developments there, and Americus Real Estate Investments – the latter of which carries Schatte’s middle name. Whitmire reported making at least $135,000 from those investments on his disclosures, though he declined to divulge the exact figure.

“Schatte’s never been convicted of anything, and it’s unfortunate that you don’t recognize that the man’s done nothing wrong,” Whitmire said. “In fact, the feds dismissed the charges and, obviously, none of that had anything to do John Whitmire.”

Schatte is now vice president at Stonehenge Holdings, a firm specializing in “developments for public entities with an emphasis on” public-private partnerships, according to its website. The city’s website shows Stonehenge is registered as a potential vendor on city contracts, raising the prospect that Schatte’s firm could seek city work under a Whitmire administration.

A family affair

In January 2022, less than two months after her father announced he would run for mayor, Whitney Whitmire started a government affairs firm with Lindsay Munoz, then the head of public policy and advocacy at the Greater Houston Partnership, the region’s main business group.

Whitmire has represented clients in Austin since 2006, but her portfolio has grown considerably in the last two years. She took in between $344,000 and $717,000 this year representing a roster of seven clients in Austin, roughly double the annual haul she’s reported for most of her lobbying career, according to state records.

Several of those clients are backers of the Whitmire mayoral campaign, including the Houston Police Officers’ Union and Landry’s, the restaurant chain of Tilman Fertitta, the billionaire Rockets owner who hosted Whitmire’s campaign kickoff fundraiser.

The firm’s owners say they will shut down that side of the business if the senator prevails, though they will continue lobbying at the state level, where a number of potential clients also do business with the city of Houston.

Wheat, of Texans for Public Justice, said that “if they are good to their word on that, it’s about as best we could do in the state of Texas,” where there are few major lobbying restrictions.

Source link

credite