The Alaska Basin addition to the Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge in the Centennial Valley encompasses more than 53,000 acres, including 32,350 which are designated wilderness. Photo courtesy USFWS

by David

Tucker

southwest corner, a windswept steppe and rolling sagebrush sea provide critical

habitat for iconic species like pronghorn, sage grouse and arctic grayling. This

landscape is also home to large-scale, multi-general agricultural outfits that

face mounting economic and social pressure as markets shift and land use

changes. It’s here that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has proposed the Missouri Headwaters Conservation

Area, a regional effort

to protect this landscape from the subdivision and sprawl seen elsewhere in Greater

Yellowstone.

The High

Divide, as this area is commonly called, is a sprawling mosaic of working

ranches, family-run agricultural operations, state and federal public lands and

private conservation easements. By stitching together up to a quarter-million

acres of this special landscape, the Service hopes to further protect threatened

wildlife and safeguard precious water resources, all while allowing agricultural

operators to continue doing business.

“Subdivision

for residential development is the number one threat,” said David Allen, realty

specialist with USFWS, “and the species that the agency is focused on all

currently exist on this landscape. Movement corridors are there and in place

largely thanks to the stewardship of private landowners managing working

ranches that have tremendous benefit for wildlife.”

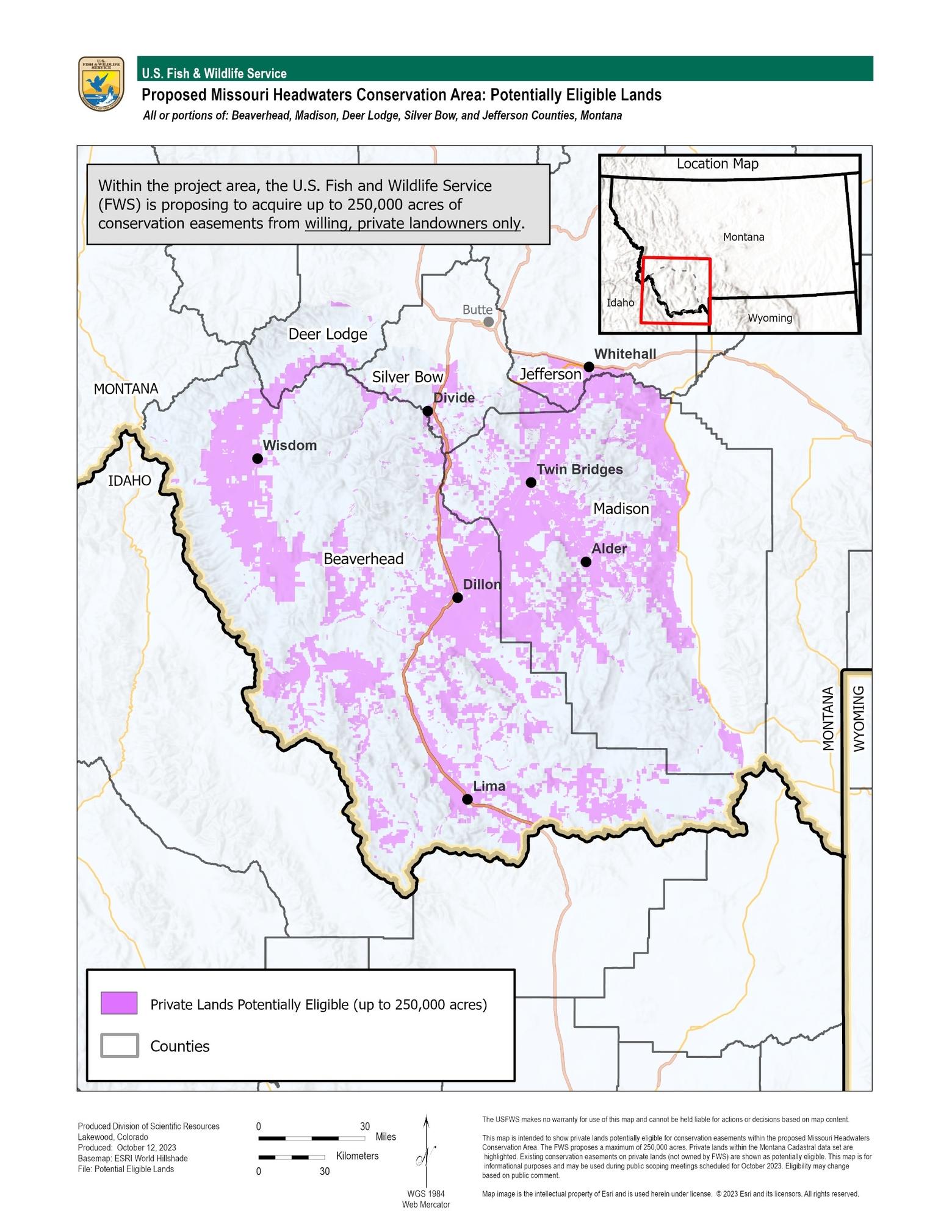

The

boundaries of the Missouri Headwaters Conservation Area, as currently proposed

by the Fish and Wildlife Service, would stretch from the Madison Valley in the

east, north to I-90, west to the Beaverhead Mountains and south to the

Centennial Range. While the entire

landmass being considered is roughly 5.7 million acres, much of it is already

managed by federal agencies or fails to meet program criteria, leaving about

1.6 million eligible private acres.

Map courtesy USFWS

1.6 million acres, USFWS is proposing to set a goal of 250,000 acres under conservation

easement over a multi-decade timeline. The Land

and Water Conservation Fund

would provide most of the necessary funding. “Conservation Areas have a very

specific meaning,” Allen said. “They give us the ability to work with willing

landowners to purchase conservation easements. They don’t limit mineral rights

or access, and include no further regulation. We just want [landowners] to keep

doing what they’re doing.”

Across

Montana, four USFWS Conservation Areas exist already—the Rocky Mountain Front,

the Swan Valley, the Lost Trail in northwest Montana and the Blackfoot Valley. “Easements

are perpetual, protected under property law,” Allen said, “and as new

challenges to wildlife and habitat conservation have emerged, our easement

program has adapted and diversified to meet these challenges. Conservation

Areas have proven to be an effective approach to conserving fish and wildlife

habitat.” Once a Conservation Area is established, it becomes a unit of the

National Wildlife Refuge System, although any included lands remain private

property and activities currently allowed there can continue, Allen added.

While the Missouri

Headwaters Conservation Area could add significant acreage under easement, it

is hardly the only regional effort aimed at the preservation of working

landscapes that benefit wildlife and other natural resources. “[The Nature

Conservancy] established our High Divide Headwaters program in 1998,” said

program director Jim Berkey, “and TNC currently holds 66 conservation easements

in the High Divide totaling just over 265,000 acres.” By partnering with

willing landowners, “TNC has piloted innovative habitat restoration approaches,

especially in riparian and sagebrush systems, on both private and public

lands,” Berkey said.

“The more these landowners can benefit from this, while simultaneously protecting the landscape, protecting the wildlife that live there—to me it’s just a win-win.” – Chad Klinkenborg, southwest manager, Montana Land Reliance

often the case, partnership, collaboration and networking has been critical to

success. “Since 2017, we have served as a lead for the Southwest Montana Sagebrush

Partnership, a

coalition of public land management agencies, watershed groups and landowners

that has greatly increased the pace and scale of restoration work addressing

key threats to southwest Montana’s sage steppe,” Berkey continued. “We face two

big challenges; economic forces—land values, commodity values—that threaten

family-based working ranches, the operations that steward our most productive

valley-bottom lands that tie public lands together and also sustain our rural

communities. And environmental forces like drought, cheatgrass and wildfire that

challenge the resilience of our natural and social systems.”

“We’ve

been working in this landscape for quite a while and are contacted by a lot of

landowners who are interested in conservation projects, including easements,”

Berkey said. “We have a pretty good sense of demand as time has moved on and

that’s been on the increase. That interest in easements far outstrips what we

can do, both from what we have a capacity to do as staff, but also what funding

resources we can tap into.”

Conservation Area would expand the pool of available funds to include allocations

from the Land and Water Conservation Fund, and Chad Klinkenborg of Montana

Land Reliance is

optimistic about that potential financial tailwind. “By bringing more funding

into the landscape, it gives landowners another tool and another organization

to potentially partner with to monetize their private property rights,”

Klinkenborg said. “It brings more funding to southwest Montana and it brings

more opportunities for landowners to utilize, if they want to.”

“To me

it’s a positive,” he continued. “The more these landowners can benefit from

this, while simultaneously protecting the landscape, protecting the wildlife

that live there—to me it’s just a win-win.”

public scoping period concluding on November 27, Allen says now is the time to review the proposal and submit public comment. “We’re

in the early stages,” he said. “And this is just one piece of the puzzle—it’s

going take a variety of solutions and efforts.”